If you’ve been around triathlon for any length of time you’ve probably heard the saying or seen a shirt that says “Why be bad at one sport when you can be bad at three?!”. And for the most part, it’s funny because it’s true. We’ve decided to participate in a sport comprised of three disciplines that are generally quite challenging in and of themselves. But hey, we like to do difficult things, right?

As much as we think of triathlon as swimming, biking, and running. My goal in writing this is to get you to adapt your outlook on training and racing. To grow and improve in the singular sport of triathlon. If successful, you’ll view each discipline through the lens of the whole (triathlon) while maintaining focus on the task at hand (swim, bike, run).

What is your strength? Are you a natural-born swimmer, a great bike-runner, or maybe your strength is your strength (mind or body)? Whatever they are, many of us tend to fall on one end of the spectrum when it comes to thinking about our strengths and weaknesses in triathlon: “maximize your strengths, minimize your weaknesses” or “ignore the strengths (because they’re already strong), hyper-focus on your weaknesses.” If you’re a former cyclist with some running under your belt, continuing to build your bike-run base and just “getting through the swim” can be a common approach. Conversely, someone with a swimming background might say, I don’t need to swim very much, I’m going all-in on the bike and run. It’s the longest part of a triathlon anyway, and the swim will be fine. Honestly, there is great merit to both of those mentalities. It can be a crucial first step to identify those strengths and weaknesses so you can develop a plan to achieve your goals. My main assertion today is to shift our viewpoint on those two extremes. And articulate how being overly focused on any one or two disciplines can cause your overall ability as a triathlete to suffer. Finally, create an approach that combines a focus on both weaker and stronger disciplines so that you can be the best version of your triathlete self.

Let’s take that first situation as a case study. We’ve got a newer triathlete who has a strong background in cycling and has some natural ability on the run. Other than recreationally hasn’t had much time in the pool. “Adult-onset swimmer” as it is often referred to, is when an adult takes up swimming later in their life. This is often contrasted with the athlete who was in the water at age 3, had formal instruction, and has been doing double swims each day since. Most of us find it very difficult to learn and improve significantly enough to ever have the same skill and ability as that lifelong swimmer. And so is often the case, we insert one of the two approaches above. Swim constantly, or do the bare minimum to get by. Since the swim tends to represent both the shortest portion of a triathlon, as well as the most stressful part. Both of these tendencies are understandable.

Let’s play this out for the situation where this person decides to do a reasonable amount of swimming but primarily puts in lots of bike-run hours. Their technique has steadily improved along with their endurance. Enough to complete the distance required for their upcoming race with no problem. They leave it at that, maybe going down to one long and one short swim per week to make more time for the bike and run. Having followed this approach for the build to their big event… Imagine this race scenario, they come to the race venue, to find a very sunny but windy day, and they hear that this water has various currents throughout. Instantly, their heart rate is rising. Did I bring the right goggles for the sun, this wind is kicking up the chop in the water, will I make the cut-off with these currents? But they have a plan, they’ve done sufficient swim training. It’ll be fine as long as they can get to the bike, then they’ll fly! The swim starts, thankfully it was a rolling start so the physical beating was kept to a minimum. But they still went out a little too hard, and yeah, they can feel the mini-waves and current already. So they increase the effort but feel the fatigue setting in. Despite all of the adversity, they make it to the halfway point of the swim realizing their energy is waning. The wetsuit is constricting, and they still have a long way to go. They persevere, and just get to the bike! They adjust their effort to try to conserve as much energy as possible, but with each passing buoy, they just want it to be over. Finally, they reach the steps, get their bearings, and begin the run to transition onto the bike. As with everyone, their heart rate spikes from the chaos of transition. Onto the bike, and here is the moment a sinking feeling sets in… their bike strength seems to be totally zapped. They spend the first ten miles just trying to get their heart rate down. Then comes the first big climb, and all of that easy riding to calm themselves is lost, as it spikes again. Another match was burned. This goes on for quite a bit longer. Smartly, they’ve now adjusted their goals on the bike to make sure they finish and have something left for the run. Unfortunately, much of that biggest strength went by the wayside. Then comes the run. How will they finish the run, they think. They feel some fresh energy now that they’re using some new muscle groups. But the times they pushed on the bike to reach their normal pace or power numbers really took a lot out of them. So the run plan needs to be adjusted considerably as well.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t a hypothetical case study, this closely mirrors the race report from my first 70.3 race. But I won’t belabor the point any longer, as you’re hopefully seeing the pattern. That brutal swim was the eventual undoing of the rest of “their” (my) race. Certainly, there were conditions or circumstances that can disrupt even the strongest of swimmers. But ultimately, they weren’t able to take advantage of all of that extra bike and run training they fit in.

So how could this have looked different? Should they have switched to swimming 5 times a week, or scrapped that extra bike in favor of doing drills in the pool? Should they have let their bike volume wane a bit to steadily build up their swim well beyond the race distance? The answer to all of these might be “yes” or “it depends.” The thing that’s so beautiful about the triathlon is how much all three disciplines work together. Swim fitness gives you a bigger engine for the bike. Core work helps your body position and form on the run. The leg strength gained on the bike builds some resiliency for the run. In this scenario, we must recognize that there is a point at which the improvement in the swim, in and of itself, will begin to reach a point of diminishing returns. That is, if their current pace is 2:00/100yds, in the short term, the likelihood of significantly raising their speed is quite low. However, and here is the magical thing, can they gain enough fitness to do that same 2:00/100yds easier. Given that energy management is so crucial to long-distance racing. If this person can finish that same swim, at the same time. But starts the bike fresh enough to take advantage of that strength, they’ve effectively improved their triathlon performance despite not “being faster” in the swim. So as they approach their training, this could mean adding additional time dedicated to their swim performance. Not primarily to have a faster pace time, but to set themself up for the bike, and in doing so, now their bike strength can be fully realized.

One more example with the bike and run might help drive this home. Let’s say you push hard on the bike, and have your best split to date. Sure, you lumbered up and down the climbs and nudged above your goal power or effort levels. But you can wear that bike split as a badge of honor from here on. You cut your goal time by 10 minutes, an outstanding step in the direction of a new race PR. But it’s time to run, and you’re feeling great after that ride. In training, you’ve consistently run 10-minute miles, and are confident that pace is doable for the duration. You even have trained to incorporate 30-second walk breaks through aid stations. The first few miles go well, you’re still riding high from the bike. Then suddenly the extra effort there is starting to set in. Those walk breaks start to lengthen bit by bit as does your pace. First, they bump up to 60 seconds per mile. Then a couple of minutes, and before you know it, you’re doing 5 minutes on, 5 minutes off. Were over even 5 kilometers you’ve more than lost that 10 minutes you gained on the bike. Extended out to a half marathon, or Ironman run course, you could be talking 20-60 minutes added to your run split and overall race time.

All of this isn’t to say that all races go perfectly, if anything, race plans always change on race day. You adapt your approach to the conditions, how your body is feeling, and many other factors. More importantly, times aren’t everything, this isn’t primarily about goals or placement or times. But about having the best race you can!

The key takeaway here is when we’re overly focused on thinking of the discipline of swimming, biking, or running, we can end up sabotaging the overarching sport of triathlon. This can occur on the macro-level as illustrated in the example above. Or it can even happen on the micro-level in how you pace yourself. Oftentimes, even with the best intentions, you might ask yourself “how can I improve on riding hills?” or “What’s the best way to lower my run time?”. And understandably your brain jumps to “well, it must involve riding hills harder” or “getting more run volume in”. Of course, that is part of the equation. But counterintuitively, it likely involves looking at the other disciplines and your performance in those. How the swim can be improved to help the bike and ultimately help your triathlon. Or going easier on the hills so that your legs aren’t burned for the run. Recognizing the big picture as the primary focus can allow you to make more strategic training and racing decisions for each discipline to better the overall result.

So finally, you might be thinking, “yeah, that makes sense for the swim and the bike, because there is something after those that will be positively or negatively impacted”… But what about the run, nothing comes after that. How does that fit in?” Not surprisingly, the same principles apply but self-referentially. That is, we often exhibit similar tendencies in how we approach pacing the run. I’m confident that I’m not taking a risk to say that the vast majority of us when left unchecked, go out too hard on the run. Much too hard. Both in training, and certainly in racing. It’s understandable, that you’re relieved to be off the bike, and if you’ve paced both the bike and the swim well (see the section above!). You’re probably feeling fresh and ready to go. On top of the fact that you’re amped up coming out of transition. Everyone is cheering for you, and naturally, you come out hot. A quarter-mile of this is no big deal, but if you let that linger on for the first quarter of the run, maybe even the first half. You’ve now put yourself in a hole that is very difficult to climb out of. And ultimately, it means you’re in suffer mode for the remainder, and definitely not finishing stronger than you started.

This can take an immense amount of discipline, to go easier when you feel you can go harder. To hold yourself back when everything else is telling you to push. Again, this isn’t about having the fastest first mile of the run. It’s about having the best run from start to finish. It involves letting ego go and structuring your training runs to start easy and finish hard. Letting the race plan (not your feelings) dictate your actions.

Clearly, triathlon requires a significant amount of discipline, skill, and fitness in three individual and unique sports. Each one demands its own attention and focus. Acknowledging our sport as one comprising three disciplines can allow you to approach it with the big picture in mind. While opening doors to tactics and strategies that will help you be not only a great swimmer, biker, or runner, but a phenomenal triathlete!

Happy Training!

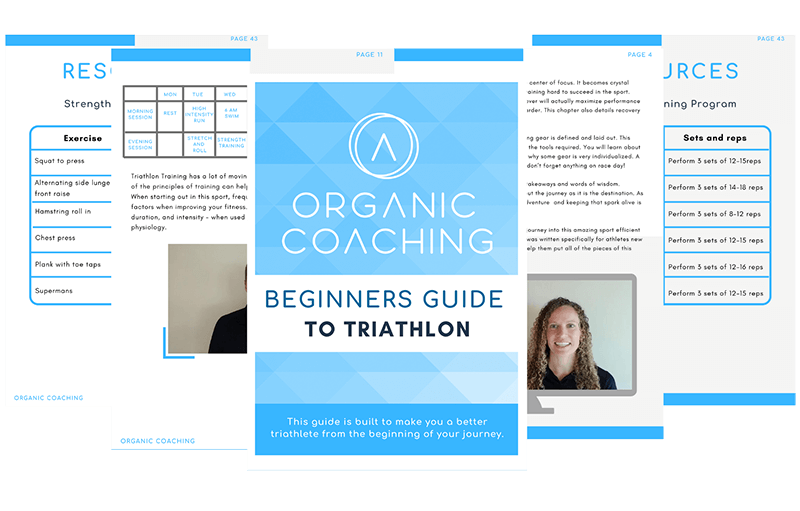

Carly and Tyler Guggemos built Organic Coaching in 2014 with a simple philosophy that works. The idea is to take what you have and grow it to get faster, fitter and stronger. And to do it with the time you have – not the time you wish you had.

For athletes who are ready to take their training to the next level while still thriving and succeeding in their professional and family life.

Copyright © 2024 Organic Coaching LLC